Why are investors hoarding cash?

Cash is often considered to be ‘king’, because of its unparalleled liquidity, flexibility and stability. Unlike other assets, cash can be used immediately without conversion or cost, and is considered safe. But do we hold too much of cash?

This question popped up again when I read recently that Japanese households hold approximately $7.5 trillion (¥1,118 trillion) in cash and deposits, accounting for more than 50% of all Japanese household assets. As an investment professional, this figure is astonishing to me. But it did prompt me to look at the equivalent figure for households in the European Union. There I found they hold approximately €11.6 trillion in currency and deposits, meaning over 30% of assets are held in cash and deposits. That is also absurdly huge!

Compare this to the US, where the absolute figure is a massive $17.8 trillion in cash, deposits and money market funds. But as a proportion, it is much lower, at around 10% share of US household assets.

Looking at these numbers got me thinking. Why do people hold so much cash?

What are fund flows telling us?

The recent period has been exceptional. Given the current interest rate environment, and the painful equity and bond sell-offs in 2022, it might not be surprising that I have observed more and more of our investors allocating to cash over the last three years.

Fund flow data, courtesy of Morningstar, corroborates this position. Money market funds dominated, at 42% of net flows, raising $593 billion over the last three years. Fixed income is running closely behind at 39% of net flows or $539 billion, as flows have picked up over the last 12 months (with Active Fixed Income funds a favourite choice).

Why is this?

Notwithstanding the need for an investment professional to manage or advise on your money, investing typically requires three core requirements from the end customer: money, time and risk taking. If you alter, remove or add to any one of these three things, it can demonstrably alter your return path.

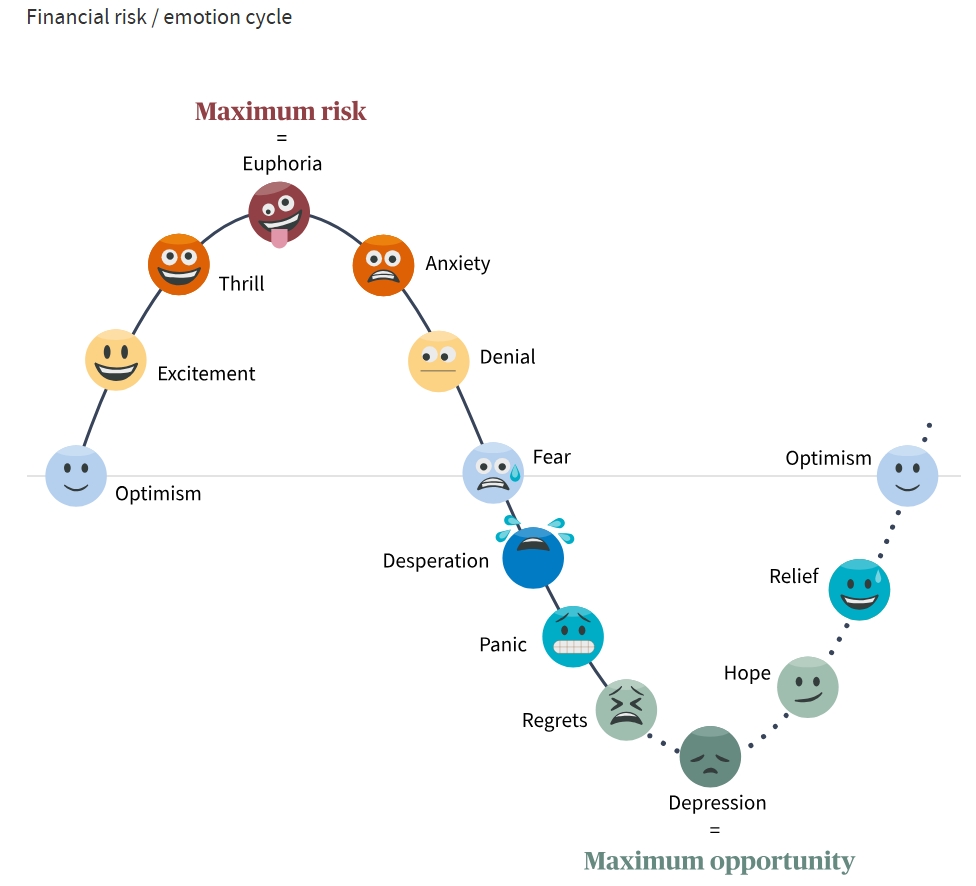

In my experience, unfortunately retail customers tend to jeopardise all three of these things at the worst possible time. One big reason for this is driven by the powerful subconscious forces of irrational behaviour, which cause investors to stray from their original goals.

Find out more about market driven emotions >

Step in behavioural psychology! According to some studies, researchers have identified more than 150 cognitive biases that can affect decision making. These biases, or irrational ‘errors’, are programmed into people’s brains and affect their decision making processes. Humans are imperfect creatures (yes, even me!) and are often prone to these biases. And particularly during times of stress.

When retail investors are formulating their portfolios, they will likely exhibit biases. You will see some of them, such as overconfidence bias (overestimating their knowledge and abilities, leading to excessive risk-taking), confirmation bias (seeking only the information that confirms their view), anchoring bias (relying too heavily on the first piece of information they receive) and herding bias (making decisions based on popular trends). They can lead to excessive greed, as well as unrealistic expectations on how the investment should perform and the time needed for it to do so.

Unintended consequences

As a result, when times are bad investors either sell out entirely or don’t reinvest at the opportune moment. In my view, they exhibit the kryptonite of all investment biases: loss aversion (where pain of losing money is felt more intensely than the pleasure of gaining the same amount). In fact, studies have shown the pain felt from a loss is nearly twice as much as the pleasure felt from a gain.

Find our more about behavioural biases >

So can we really blame a human being for exhibiting these behaviours, when they are built into us? If I reflect these biases back to my core requirements of investing, what we tend to see is:

- Money – investors tend to make redemptions or stop investing during times of stress.

- Time – investors often have unrealistic expectations of how long it takes to generate their required returns, thereby becoming too short-term in their decision making.

- Risk – any bad experiences will likely lead to overly conservative investment strategies and missed opportunities.

Taken all together, these behavioural biases, combined with holding too much cash, could lead to sub-optimal outcomes for investors. In my next article I’ll delve into this in more detail, as well as what we, as an investment industry, can do to help investors reach their long-term goals.